The Movement Action Plan (MAP) is a tool to help you understand the progress of a social movement. Developed in the 1980s by Bill Moyer, it describes eight stages of successful movements and four different roles activists play in a social movement.

The MAP is based on seven strategic assumptions, which strongly relate it to nonviolence and nonviolence theories of power and social change:

-

Social movements have been proven to be powerful in the past, and hopefully they can be powerful in the future.

-

Social movements are at the centre of society. Social movements are based on society's most progressive values: justice, freedom, democracy, civil rights. Although they oppose the state or the government, social movements are promoting a better society, not working against it.

-

The real issue is “social justice” versus “vested interests”. The movement works for social justice and those in power represent vested interests.

-

The grand strategy is to promote participatory democracy. Lack of real democracy is a major source of injustice and social problems. In the fight for the movement's goal, developing participatory democracy is key.

-

The target constituency is the ordinary citizen, who gives power to powerholders by consent. The central issue in social movements is the struggle between the movement and powerholders to win the support of the majority of the people, who ultimately hold the power to preserve the status quo or create change.

-

Success is a long-term process, not an event. To achieve success, the movement needs to be successful in a long series of sub-goals.

-

Social movements must be nonviolent.

Eight stages of social movements

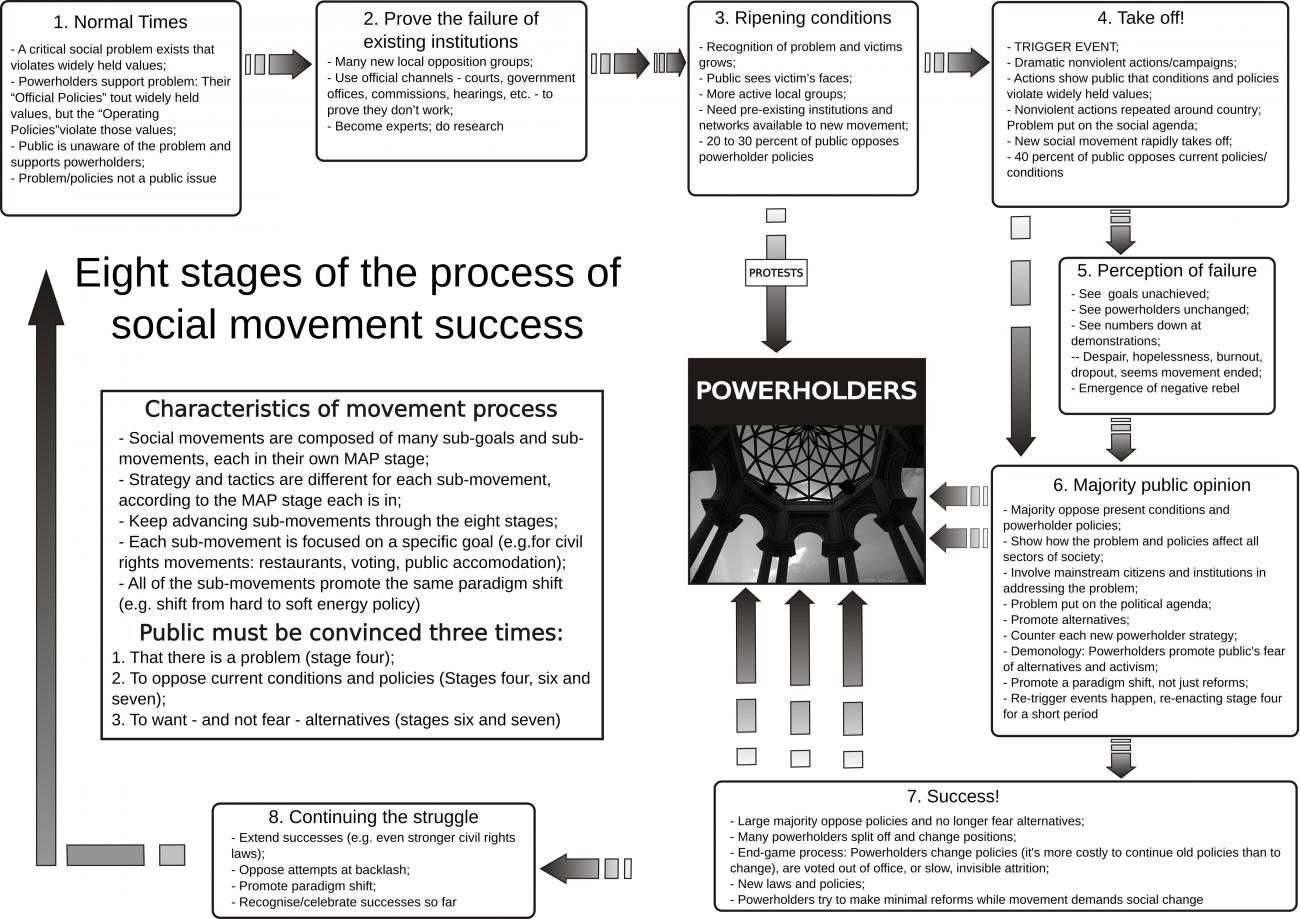

One of the two key concepts of the MAP are the eight stages of social movements. In each of these stages, specific strategic objectives are important to move a movement forward to the next stage. While this can be challenging – we cannot just jump to success – it is at the same time important to understand what can realistically be achieved at what stage of the movement.

A movement begins without knowing it. In Stage 1, business as usual, the main aim of movement groups is to get people thinking, to show that there is a problem.

The next step is to show the failure of established channels (Stage 2). Using hearings, legal processes, participation in administrative proceedings, and so on, the movement has to prove that these institutions won't act for the people to solve the problem – that people will have to act themselves.

This leads to ripening conditions (Stage 3) for the development of a social movement. People start to listen and form new groups, small civil disobedience actions start to dramatise the problem. The powerholders get a bit irritated, but mainly go on as usual.

If the movement does its homework well (organising new groups, networking and coalition-building) it can take off (Stage 4) after a trigger event. This might be organised by the movement – the occupation of the construction site at Wyhl, Germany, in 1974 triggered the German anti-nuclear movement – or something done by the powerholders. The trigger event leads to massive demonstrations, large campaigns of civil disobedience and extensive media coverage. Although the movement has very likely won a lot of public sympathy the powerholders usually won't give up at this stage.

This often leads to a perception of failure (Stage 5) by many activists. This is enhanced by decreasing participation in movement events and negative media coverage.

But at the same time the movement is winning over the majority (Stage 6). Until now, the movement has focused on protest; now it is important to offer solutions. A majority of society agrees that there is a need for change. But this alone does not mean there will be change. It is now important to win the struggle over the kind of change to be made.

The powerholders will try to cheat the movement, increase oppression, play tricks. The movement must aim to stop the tricks and promote an alternative solution.

Actual success (Stage 7) is a long process and often difficult to recognise. The movement's task is not just to get its demands met, but to achieve a paradigm shift, a new way of thinking. Just to turn off all nuclear power plants without changing our view on energy only moves the problem from radioactivity to carbon dioxide. Just to get some women into positions of power doesn't change the structure of a patriarchal society.

After the movement wins – either by confrontational struggle or a long-term weakening of the powerholders – the movement needs to get its success implemented. Consolidation of success and moving over to other struggles (Stage 8) is now the movement's task.

The four roles of activism

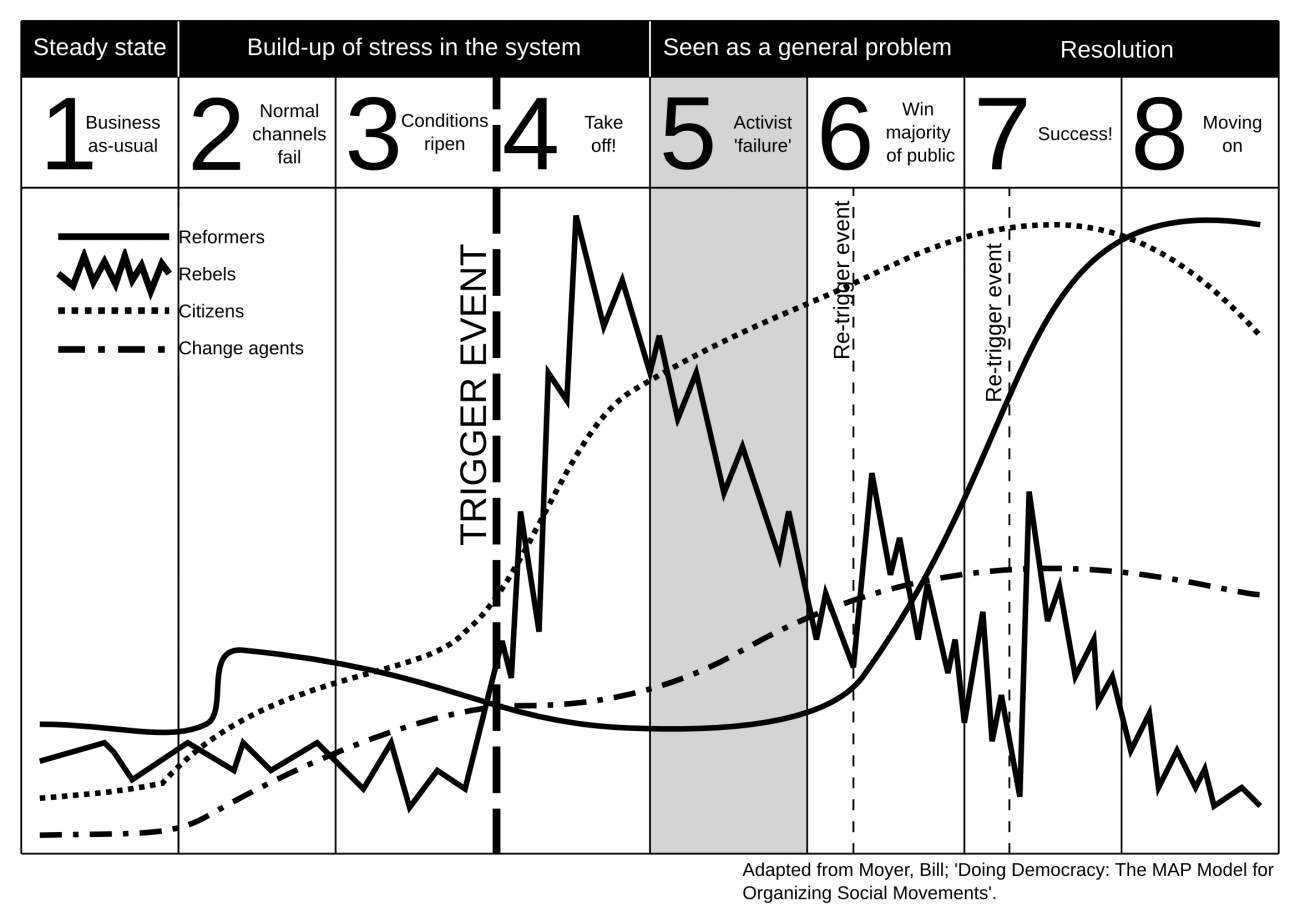

The second central concept of the MAP are the four roles of activism. Each of these roles has its own relevance, which can shift through the different stages of a movement. But all roles need to be present and work efficiently for the movement to succeed. In addition, each of the roles can be filled in an effective or ineffective way.

The rebel is the kind of activist many people identify with social movements. Through nonviolent direct actions and publicly saying “no”, rebels put the problem on the political agenda. But they can be ineffective by identifying themselves as the lonely voice on society's fringe and playing the militant radical. Rebels are important in Stages 3 and 4 and after any trigger event, but they usually move over to other ripening movements in Stage 6 or later.

Reformers are often badly valued in movements, but they are the ones who prove the failure of existing channels or promote alternative solutions. However, they often tend to believe in the institutions or propose reforms too small to consolidate the movement's success.

Citizens make sure the movement doesn't lose contact with its main constituency. They show that the movement acts at the centre of society (teachers, physicians, and farmers participating in the Gorleben protests), and protect it against oppression. They can be ineffective when they still believe in the powerholders' claim to serve public interests.

The change agent is the fourth and somehow key role in any movement. They promote education and convince the majority of society, they organise grassroots networks and promote long-term strategies. They too can be ineffective by promoting utopian visions or advocating only a single approach. They also tend to ignore personal issues and needs of activists.

Many activists and groups identify primarily with only one or two of the four roles, because each involves different emotions and attitudes, beliefs, ideologies, sources of funding, political and, often, organisational arrangements. Activists can be critical - or even hostile - to those playing other roles. Activists tend to consider the roles they play as the most important and politically correct one, while viewing other roles as naive, politically incorrect, ineffective, or, even, as the enemy.

While there are certainly tensions between the different roles, recognising that each has its own value within a social movement is important to achieve success.

Comments

There are no comments on this article. Have you got something related to this topic, you'd like to say? Please feel free to be the first person to make a comment.

Add new comment