Today, war rages on.

Ex-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev wrote in January 2017: “It all looks as if the world is preparing for war”. He added, “wars must be outlawed, because none of the global problems we are facing can be resolved by war – not poverty, nor the environment, migration, population growth, or shortages of resources”.

How do we outlaw wars when most people only see wars on screens and when the ‘culture’ of war is an acceptable part of normal life – from addictive video games to arms sales exhibitions and the mass dehumanization of ‘the others’ who are killed daily?

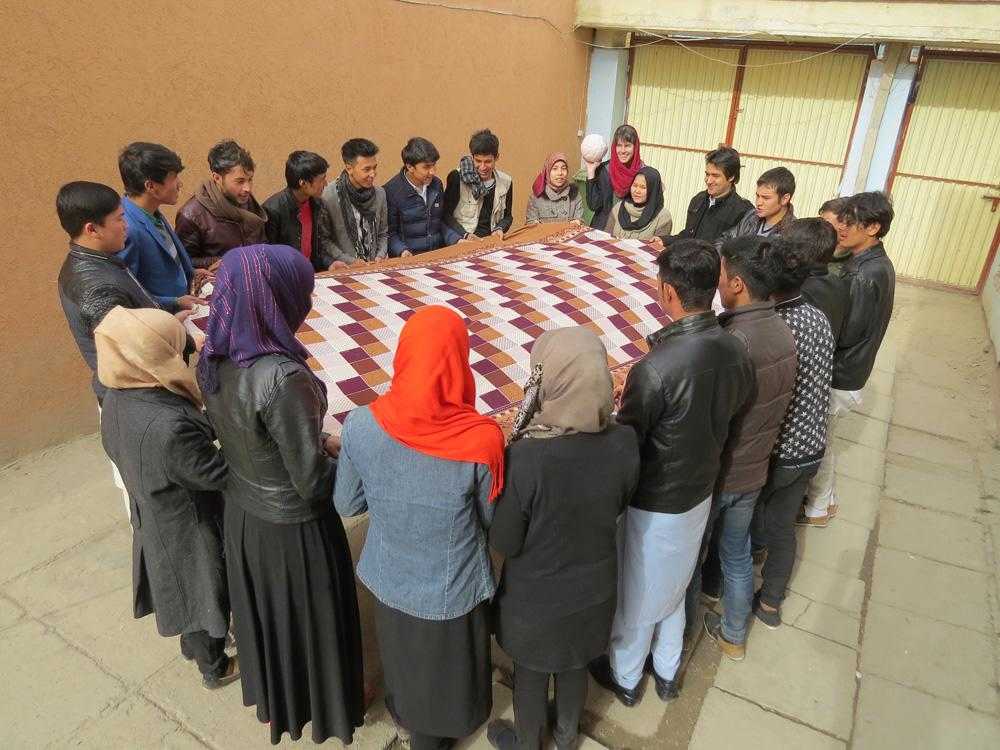

This world of wars is not the world that the Afghan Peace Volunteers (AVPs) wish to live in. The Volunteers are a grassroots group of ordinary, multi-ethnic, Afghans who seek to build a critical mass of nonviolent relationships and alternative practices to create a green, equal and nonviolent world without war. The APVs seek solutions through their grassroots work, which nurtures egalitarian nonviolent relationships and alternative practices.

The young people of the AVPs ‘relate and practice’ in 17 teams that work at the Borderfree Nonviolence Community Centre under three broad areas, with the acronym #Earth! GEN: Green, Equal and Nonviolent. The teams nurture relationships with nature and with the human family, believing that love can open all borders. They try to adopt alternatives to current ‘norms’ through:

-

using clean energy,

-

saving water,

-

mixed-gender bicycling,

-

a street kids school with 100 students,

-

a winter duvet project in which 3000 duvets are sewn (by 60 Afghan women paid per duvet sewn) and distributed to poor families in Kabul,

-

a food bank,

-

a microloans project for labourers to set up small businesses,

-

a finance and accounts system that’s experimenting with participatory budgeting,

-

a small nonviolence library, and

-

making blue scarves which symbolize their wish for ‘all to live together peacefully under the same blue sky’.

Their values and goals have crystallised gradually over the past five years. Some of the groups key goals and values are:

-

Refraining from using fossil fuels (oil, petrol, coal etc) and nuclear energy. In their place, endeavouring to use clean, renewable energy (solar, wind and hydro energy).

-

Promoting organic agriculture, for example permaculture and agro-ecology, and other methods which repair and enrich the air, water, soil and natural environments.

-

Practicing equality. Working to end the discrimination of any human being, discrimination which is based on race/ethnicity, language, gender, religion, political opinion, economic situation and other criteria.

-

Practicing and promoting more egalitarian and cooperative economies.

-

Working to abolish war.

-

Opposing the use of weapons or militaries. Supporting the abolition of nuclear weapons.

The Volunteers have come to understand the intersectionality of all causes and struggles. Many local and global problems share common or interrelated root causes. Hence, the Volunteers value the building of as many relationships as is realistically possible, so as to contribute to a critical mass movement of people needed to resolve systemic crises. The APVs are constantly figuring out how to better handle numerous challenges, in the areas mentioned below.

1. Long-term sustainability

Ecological sustainability

There is already a water crisis in Afghanistan as a result of reduced snowfall and the reduction of the Kabul groundwater level (which has dropped one metre every year over the past decade). Almost half the population suffers from a form of malnutrition. To alleviate this, the APVs are using solar energy and developing their permaculture skills, and hope to explore courtyard/kitchen gardening.

Human resource sustainability

There is a need for a larger core group of APVs with a long-term vision and commitment to its mission. The group needs to promote ‘volunteerism’, which is not a common practice in Afghanistan. Volunteer care is also crucial to retain existing Volunteers. A ‘Psychology Team’ has been working with Dr Patricia Cane and George Horan from Capacitar, an international trauma-healing organization, to begin looking at the psychological and emotional well-being of the Volunteers. The Team use practices centred on working with acupressure and ‘emotional meridians’ of the body. The Volunteers are beginning to put into place community processes for ‘volunteer and compassion fatigue’.

Financial sustainability

The APVs wish to be financially self-reliant. The groups current financial support comes mainly from nonviolent peace groups in the USA, UK and Australia, and is therefore not self-sustaining.

The Volunteers have begun the long process of building trust with local philanthropists with the hope of securing permanent premises. Over the past four years, they have tried unsuccessfully to support tailoring businesses for Afghan women. The projects were unsuccessful, chiefly because the women preferred to be paid workers rather than owners, and also because each woman’s dire financial needs motivated them towards prioritising personal and family needs more than group needs. The APVs are now learning about establishing worker cooperatives and are exploring business ideas such as selling solar power equipment and the production and sale of organic vegetables.

2. Building concrete and viable egalitarian, nonviolent relationships and alternatives; particularly in the areas of economy and education (livelihoods and minds)

Across all sectors of life, unequal and violent responses to conflict are currently more easily accessible and seem more viable than equitable and peaceful ones. Thus, the vast majority of Afghans choose or ‘flow along with’ the status quo.

The APVs are trying to build alternatives to each of the dominant norms. As a priority, the Volunteers are developing alternative learning models, such as Relational Learning Circles. Furthermore, they have plans to establish an ‘Institute of Nonviolence’ to promote fresh ways of learning in a setting that could reach mainstream academic institutions. This institute will move away from the standardised tests of the current Afghan education system. It does not want to produce students who go on to join the capitalistic neoliberal economy, ready to wage environmental, economic and military wars for the ‘bottom line’. It also hopes to promote nonviolent jobs so that young people – like those in Sultan's story below – can consider non-military work.

3. Continued healing from the psycho-social and emotional challenges of intractable violence and war

All Afghans cope with hopelessness, severe societal distrust, trauma, fears, anxieties, anger, sorrow, frustrations and ‘burn-out’. Their individual and group esteem and identities are complicated by strong survival instincts and a natural need for public affirmation. Organizational planning may be good, but if the APVs aren’t psychologically healthy, then the best-laid plans may come to naught. The Volunteers have been working with Capacitar to enable trauma healing, and as the APVs become mindful of restoring their inner selves they become ever more resilient.

The APVs practice their belief that ‘love can open every border’ by making friends across divided Afghan ethnic groups in programs such as Borderfree Atan (the Atan is the Afghan National Dance) and Borderfree Afghan Football Club. For two-to-three years up until 2015, some of the core APVs lived in intentional communities of multi-ethnic youth, an experience that will continue to instruct the group into the future.

The Volunteers also reach out to people across the world through online conversations called Global Days of Listening and Relational Learning Circles. These have helped to transform their mindsets and practices. Some volunteers have testified that such relationships have opened up their world views ‘better than any university’ could. The emphasis on relationships has also helped me and the APVs to develop Relational Pedagogy, which is, in short, learning through relationships, including those with nature.

4. Hyper-individualism, elitism, money-ism (including consumerism) and militarism in the midst of inequality and poverty

Even in civil society, a common thought is, “how will this help me to find money and be influential?”. Afghans say that “even brothers cannot trust brothers, as they may kill one another for a few dollars”. Thus, the APVs are adopting other motivations and purposes in life besides the pursuit of power and wealth. An example of an alternative ethos the APVs hold dear is to “Transform Me into We”.

Building alternatives

The APVs realize that to live differently they need to develop new ways of relating to each other, and to build viable alternatives in their everyday lives. The groups ‘leaf’ of nonviolence has two sides: one face is the nurturing of relationships, and the other the construction of small, positive, and concrete local options. Projects that have been explored over the years include providing interest-free loans for sundry shop-keeping, livestock (sheep) keeping, a confectionery, a home-made potato chip and French Fries shop, a tailoring cooperative, and various types of street-vendor businesses. Many of these businesses continue to run, and the tailoring cooperative is currently made up of seven Afghan women.

The seeds of this approach were planted about eight years ago by a few young people in Bamiyan – a central Province at the ‘heart’ of Afghanistan. They organized activities to raise their voice of non-military peace. In the ‘militarized peace’ prevalent in Afghanistan, they were seen more as naïve youngsters than as protesters. Their voices haven’t yet been heard by a disinterested mainstream media and a generally pro-military Afghan civil society. So the APVs had to create their own microscopic alternative media, using mobile phones, cameras, YouTube and Skype to connect with individuals and communities around the world. It is impossible to estimate the multiplying effect this may have had.

Making decisions together

Another example of building alternatives is the APVs’ development of egalitarian, grassroots self-governance to counter hierarchical, authoritarian governance. They have no ‘Director’ who can ‘call the shots’, which is radically different from the top-down norms of other Afghan groups. However, there are doubts over the slower consensus-building process. The Volunteers discover that the Occupy movement’s ethos of having ‘no leaders’ ironically means that every one of them is a leader. Some need to question their ambitions to be ‘better’ than ‘the other’; to be the ‘boss’ or ‘the star’. They learn to let go of the thought, “I’m definitely right, and he/she is wrong”, thereby steering away from ‘moral’ judgements.

Specifically, the APVs manage their work through a consensus decision-making processes via a Coordinators’ Team made up of coordinators from the 17 teams. Most of the teams have two coordinators, a male and a female, making up a 22-member Coordinators’ Team. There are currently around 75 active Volunteers, who put in at least eight hours of voluntary work every month. Another 50 are ‘APV Friends’, who participate in activities less frequently. The youth live in their own homes in Kabul, with the majority in rented housing in the Western part of Kabul, where the Borderfree Nonviolence Community Centre is located. Some travel to the Centre from further away.

From 2012 to 2016, the APVs established two intentional live-in nonviolence communities comprised of multi-ethnic youth. The male community reached a maximum of 16 members; however, the female community only managed to recruit three, primarily because of socio-cultural constraints. From their valuable experience, a concept paper has been written with a view to re-establishing a live-in community in the future, while working to develop the structure and work of the organization.

The work of the APVs hasn’t reached beyond Kabul as yet, although trips were made to three other provinces to build connections. In September 2017, they partnered with two NGOs to organize a “Youth on the Road to Peace Conference” in which young people from 24 out of 34 Afghan provinces participated.

Stories from members of the Afghan Peace Volunteers

Zarghuna: Nurturing nonviolent relationships with self, Nature and the human family

Zarghuna is a 24-year-old APV and journalism graduate who has recently taken on a full-time living-wage job with the group. The multiple dimensions of relationships have become clearer to her in the course of her work. She explained, “My father was killed in war. The decades of war have torn our family and societal relationships apart. I need so much to be at peace with myself and with everyone.” Once, after a disagreement among two volunteers, Zarghuna intervened and explained “even work for peace is not worth paying the price of unhappy relationships”. This is an important reminder that if activist groups become too ‘workaholic’ or ‘achievement-orientated’ then we risk overlooking relationship-building, and we may miss out on an important part of the awakening human consciousness: that we’re all related, and that if any one relationship is unhealthy, we’re less peaceful.

Zarghuna was referring to the deliberate work of healing ‘the war within’ each person. Being at peace with herself means self-care and working through her many emotions: worry for her widowed mother’s depression and multiple body aches, stresses from conservative social norms which restrict her personal development, and forgiveness for her father’s killers. Relational peace is central to the work of the APVs.

Zarghuna is part of a Permaculture Team that now takes care of two permaculture gardens – one at the Borderfree Nonviolence Community Centre and one at Kabul University. Zarghuna remarks, “In my home province of Bamiyan, the elders tell stories of how there used to be a lot more snowfall in winter. My family lives on less-than-subsistence farming, but I didn’t know how to better care for the earth and human habitats until I began to learn from Rosemary Morrow, an Australian permaculturalist, who is teaching us how to work with Nature’s patterns and designs. Nature is our teacher… I remember Rosemary telling us that the soil is a living being, so never leave it naked; that is, we should plant on soil and cover it with mulch wherever we can.”

Building small local nonviolent alternatives and constructive programs: Sultan’s Soldier Story

Ali is a member of the APVs. Ali’s older brother, Sultan, was a soldier. Years ago, while he was fighting in Kunar Province, his mother fell sick worrying about him, and Sultan became a temperamental son and brother during his home visits. After being persuaded by his mother and family, Sultan left the army for a year-and-a-half, married, and became very attached to his newborn daughter. However, there were no jobs to be had; the economic war is the other war, the silent war, and the more deadly. Sultan rejoined the army.

The cost of not having alternative nonviolent jobs is high. Tolo News reported in April 2017 that “almost 18,000 Afghan National Police (ANP) officers had been killed in battles in the southern province of Helmand over the past fifteen years.” Add another 10-to-35 police officers who were recently killed in the ‘friendly fire’ of a US/NATO air raid. This means up to 18,000 widows, and probably more fatherless children, counting only dead policemen. How about dead soldiers, and the other 33 Afghan provinces?

The last time Ali saw his brother was when Sultan had stopped by in Kabul for a night before returning to his army post in Kandahar. Sultan had no appetite as he was already missing his young daughter, so he ate very little. I was at that dinner and said, “Sultan, the moment you’re able to find some other work, leave the army.” I felt powerless, almost hypocritical, because neither the AVPs nor international peace groups had ready alternative jobs to refer Sultan to. A month later, he was killed by five bullets.

The machinery of the militarized status quo can be overwhelming. Sometimes, resisting war feels like we’re resisting ourselves, from within, where ‘war’ arises. To persevere, like all civic efforts throughout history, the APVs are trying to keep together, and to never give up.

Hakim Young – Dr Hakim (Dr. Teck Young, Wee) is a medical doctor from Singapore who has conducted humanitarian and social enterprise work in Afghanistan for more than 10 years, including being a mentor to the Afghan Peace Volunteers, an inter-ethnic group of young Afghans dedicated to building non-violent alternatives to war. He was the 2012 recipient of the International Pfeffer Peace Prize and the 2017 recipient of the Singapore Medical Association Merit Award for contributions to social service to communities.

Comments

There are no comments on this article. Have you got something related to this topic, you'd like to say? Please feel free to be the first person to make a comment.

Add new comment